A tweet from the skeptics at the Reasonable Doubts podcast inspired today’s challenge:

What do you say? How do you answer this challenge? Leave your ideas in the comments below, and we’ll hear Brett’s answer later this week.

A tweet from the skeptics at the Reasonable Doubts podcast inspired today’s challenge:

What do you say? How do you answer this challenge? Leave your ideas in the comments below, and we’ll hear Brett’s answer later this week.

I think this is looking to answer the reason for evil, isn’t it? And it seems that with point 9 that it is declaring some sort of limitation for God.

I think it is a major presumption to know what God would chose over what. There isn’t any indication that if God chose to interact with an imperfect world that it would make God any less than He is. Evil exists, not because of a limitation of God, but because God gave us free will. We, as fallible humans, have caused the evil, along with Satan and his brood, of course. Every step I take was not preplanned by God for me to take. Though God knows where my next step will take me, that step was not predetermined. And if evil ensues when we follow our own selfish desires and lose our focus on God, then it happens.

Perhaps claiming that this is the best possible world is an answer as to why there is evil in the world, but it’s a very weak and presumptuous one at best. Plus it is in some ways saying that we are not being held responsible for our sins, God is the reason we are as we are.

I can’t wait to hear other comments as I could be way off on what I read into this.

This seems pretty amateurish to me.

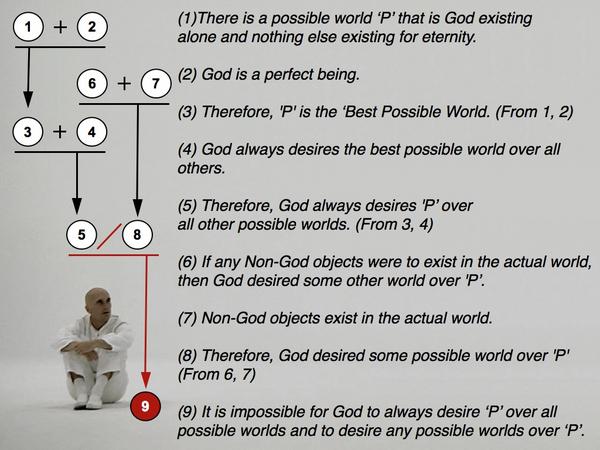

Premises 1& 2 and intermediate conclusion 3 are really nothing more than defining and constraining the meaning of “Best Possible World.” In other words, the “best possible world” is defined in this argument to mean “the possible world in which only the perfect God exists.” But what gives us warrant to define the phrase thusly? Is that really the best possible world?

This is just linguistic sleight-of-hand dressed up in a “logical argument” Halloween costume.

I don’t think that the first syllogism is in fact true. It doesn’t follow that 3) Therefore ‘P’ is the Best Possible Worlds. It is in my view, a non sequitur. Why couldn’t God create another being or entity that was perfect? If God can create a perfect being then there is no longer a Best Possible World but rather Two Equally Perfect And Equally Possible Worlds. I use this to show that the conclusion does not necessarily follow from the premises. It doesn’t follow that God would desire a world where He alone exists. Since He alone doesn’t exist then He does not desire the best world? No. What they are failing to recognize is that God not only chose the Best Possible World(which they are right that God would choose this), but that He also chooses the Best Possible Way to get to the Best Possible World which contains morally free creatures who chose to have a loving relationship with their Creator and to take their pleasure in Him for eternity. THIS is, in Gods view, the Best Possible World, which God will see that this world will in due time be a world which is actualized.

And Amy feel free to “tweak” me on if you think I’m on point or just way off base here.

This is, like, wrong on so many levels, I’m, like, what do I say, you know?

Consider this argument:

1′. There is a possible world P’ in which God exists and so does the universe.

2′. God is a perfect being.

3′. Therefore, P’ is the best of all possible worlds.

Etc.

There seems to be an equivocation on the phrase “possible world” in this argument. On the one hand, a “possible world” is a maximally describable state of affairs that doesn’t have any contradictions and is evaluated apart from God. So among the “possible worlds,” there are many that are not the best, and we are saying that God actualizes the best one.

But on the other hand, we are saying that because God is perfect, only one world CAN be actualized, which means only one world IS possible. The “best of all possible worlds” is also the only possible world there is since, if God is perfect, that’s the only world he’d allow.

So “possible world” is being used in two different senses, committing the fallacy of equivocation.

If we force the argument to be consistent by choosing one definition of “possible world,” then the argument doesn’t work. If we go with that first evaluation, then 3 doesn’t follow from 1 and 2. But if we go with the second evaluation, then the argument is question-begging because it begins with the premise that there is a possible world in which God alone exists. That’s what my parody above illustrates.

The rest of the argument is fine except that it doesn’t go anywhere. It looks like the bottom part of the argument got cut off. It looks like the argument is headed for a contradiction, which will require us to reject one of the original premises. But we could reject 1 or 2. If we reject 1, then we could replace it with something like:

1”. There is a possible world P” which also happens to be the actual world.

So the argument doesn’t really tell us anything interesting about whether God exists or about whether this is the best of all possible worlds or anything.

I just noticed that if someone were to critique this argument, that after a thorough critique, this argument is a GREAT segway to the Ontological Argument since the first two premises are the foundation for the Ontological Argument.

Alvin Plantinga’s Ontological Argument can be formulated as follows:

1) It is possible that a maximally great being exists.

2) If it is possible that a maximally great being exists, then a maximally great being exists in some possible world.

3) If a maximally great being exists in some possible world, then it exists in every possible world.

4) If a maximally great being exists in every possible world, then it exists in the actual world.

5) If a maximally great being exists in the actual world, then a maximally great being exists.

6) Therefore, a maximally great being exists.

When an atheist brings up the problem of evil, the existence of objective evil is actually a great argument for God’s existence. Similarly, the atheist’s argument here is actually a good argument for His existence. Premise 1) of their argument implies that it is possible for a great being to exist. Premise 2) of their argument implies that this great being is maximally great or perfect both ontologically and morally. Since the atheist is committed to their two premises they would have to be committed to our first two premises as well. And this would make it extremely difficult for the atheist to show our argument to be wrong given their commitment to the first two premises.

Thanks for the critiques so far guys. The inference from 1 and 2 to 3 is, I admit is a bit unclear. I plan on clarifying that point in my response – I think the denial of it is entirely available to the theist but I also think this approach also has some very unwelcome consequences that are not immediately obvious. And for those who have already dismissed the argument as amateurish, I apologize for wasting your time.

Thanks for joining us Justin! Some clarification would be very helpful. I look forward to the response.

I agree that 3 does not necessarily follow from premises 1 and 2. The challenger needs to give me more reason as to why I should accept that.

I think the problem here is that it is not possible to determine what would constitute the greatest possible world ‘P.’ The first objection that the atheist typically brings to the ontological argument that Jonathan laid out is that they believe this could prove the existence of the greatest possible anything. To give you an example, in William Lane Craig’s debate with Victor Stenger, Stenger proposed, “Couldn’t I use the same logic to prove the existence of a greatest possible pizza?” Craig’s response was, “No, because the idea of a greatest possible pizza is logically incoherent. A greatest possible pizza would be metaphysically necessary in it’s existence, therefore it couldn’t be eaten, and therefore it wouldn’t be a pizza.” Simply put, material things could not have greatest possible properties.

In the same way, I’m not convinced one could determine what it takes to constitute the greatest possible world. The properties for a greatest possible being are clear (omniscience, omnipotence, etc.) but there are many possible world’s containing properties that appear to be totally neutral as to whether they make it the greatest possible world.

My biggest problem is that the ‘best possible world’ assumes certain factors: God exists alone and nothing else exists for all eternity. By providing a definition of this ‘best possible world’, you constrain any conclusions drawn to the limits of your assumption. The problem is that if you remove your assumption about the nature of the ‘best possible world’, then your later conclusion drawn from the existence of non-God things falls apart. I don’t see that this particular argument can be made to work in this form. Justin – I assume you are the originator of this? If so, I’d be curious to see the results of a reworked version of this chart.

This might help clear things up a little bit.

1. There is a possible world (P) where God exists and nothing else exists.

2. God is the best possible being – morally and ontologically perfect – All of his properties are all the great-making properties to their maximal degree.

3. Therefore, (P) is the best possible world. (A world composed entirely of all great-making properties to their maximal degree and no other properties.) Nothing exists that isn’t a maximal perfection.

Justin, it seems to me that the only way 3 follows from 1 and 2 is if you are defining “possible world” in a peculiar way. You seem to define a world as possible only if God actualizes it. If God doesn’t actualize a world, then that world is not possible. But that makes your argument circular since the only way you could know that P was possible is if you already knew it was the best of all possible worlds.

What if I began with this premise:

1′. There is a possible world (P’) where God exists and so does the universe.

If a world is only possible if God actualizes it, and if,

2′. God is the best possible being and only actualizes the best possible worlds,

it would follow that:

3′. Therefore, (P’) is the best of all possible worlds.

There doesn’t seem to be any non-question begging way to choose between 1 and 1′, which makes me think the argument is fallacious.

But maybe you are making a different argument and are just characterizing it in an odd way. Maybe you are defining the best of all possible worlds as a world in which only the greatest of all great-making properties are instantiated. In that case, your argument should look more like this:

1. If God is the best of all possible beings, then God only actualizes the best of all possible worlds.

2. The best of all possible worlds is a world in which only the greatest of all great-making properties is instantiated.

3. Therefore, if God is the best of all possible beings, then God only actualizes a world in which the greatest of all great-making properties is instantiated.

4. God is the best of all possible beings.

5. Therefore, God only actualizes a world in which the greatest of all great-making properties is instantiated.

If that’s what you mean to argue, then I think the biggest problem with your argument is your definition of the best of all possible worlds. Your definition is incoherent because if we took your definition seriously, then we’d have a world that contained courage but also didn’t contain courage. It would contain mercy, but it would not contain mercy. Etc. The reason is because courage and mercy are great-making properties but they cannot exist unless there are other properties exist that are not the greatest of great-making properties. So courage would exist because it’s a great-making property, and courage would not exist because there couldnt be anything to fear. There has to be something to fear before there can be such a thing as courage. There has to be such a thing as wrong-doing before there can be such a thing as mercy.

If God is the greatest possible being, then the greatest possible good would be the display of all of God’s glory, which would mean the exhaustive actualization of all of God’s attributes. That would not be possible if God were the only being that existed. If there were no other beings in existence, God could not demonstrate or act upon his mercy, his wrath, his kindness, his justice, etc.

I would rather define the greatest of all possible worlds to be a world in which the greatest good is realized to the fullest extent. But that is a world in which there is evil and suffering.

So either way, I just don’t think you have a good argument.

//If God is the greatest possible being, then the greatest possible good would be the display of all of God’s glory, which would mean the exhaustive actualization of all of God’s attributes.//

I was just going to bring this up Sam. For example,it would be meaningless to say that God is omnipotent since, according to Justin, God alone would have to exist in a world in order for that world to be called the Best Possible World. God’s omnipotence loses all meaning since He couldn’t exercise His power since nothing else exists. And would it be fair for us to say that a being that could not exercise His power is actually the greatest maximal being? This concept of God is incoherent. This concept of God is not the greatest maximal being since God exercising His power would not be the best possible world.

Also, as per Craig’s remark about the greatest possible pizza being logically incoherent – I don’t buy that. A pizza is not a pizza in virtue of it being possible to eat it – that seems terribly wrongheaded. A metaphysically necessary pizza does seem a bit silly, but clearly not for the reasons Craig gives.

I have a different objection to what Craig said.

“No, because the idea of a greatest possible pizza is logically incoherent. A greatest possible pizza would be metaphysically necessary in it’s existence, therefore it couldn’t be eaten, and therefore it wouldn’t be a pizza.”

If a pizza that couldn’t be eaten is not a pizza, then a metaphysically necessary pizza is not possible. But that doesn’t mean there couldn’t be a greatest possible pizza. It just means that the greatest possible pizza wouldn’t be a necessary pizza.

Sam, that is not how I am defining possible worlds. I am using mainstream modal semantics. A possible a world is any maximally consistent set of propositions – mere logical possibility. I am saying it is possible that God chose not to create a world – this preserves the creation act as a free choice of God’s rather than a necessary outpouring of action.

Then your third premise doesn’t follow from your first two premises.

I think we can have fun analyzing the concept of “best possible worlds.” Up to this time, I’ve noticed only discussing the BPW as a static proposition. Once formed, how will it fare in temporal situations? Does the BPW endure change? No would seem ridiculous. A world in motion would be far preferable to a still-life. But yes would be a difficult proposition. If change must come, will such change be improvement? If so, we never began with the BPW, unless improvement would be an in-built quality that makes the BPW “best.” But a notion of improvement would be against scientific prinicples of enthropy. I would like to ponder further possibilities, but I would view the BPW as either a marvel of existence that defies scientific analysis, or something that science must study, but never fully comprehend.

One weakness of the whole line of argument is the introduction of the “non-God” entities at 6 and 7. I don’t believe the definition of such was presented, at least not with a degree of exactness that grants that if God then non-God is impossible. This was the point of the argument that got rather wierd. God, who is extreme in His perfection could grant non-God entities as matters He could resolve in His fashion. The one non-God entity that would come to mind is sin. To create a world would allow for free agent humans to go forth and foul up, but not without God’s ability to rectify the matter in His manner on His schedule.

The lack of definition undermines the whole argument. In that the problem of evil hovers close about this argument makes it a fine study of the ontological nature of God as creator, but in the end, Job conceeded God’s sovereignty in the case of justice. We can do the same in the case of creation.

I hope you can forgive me for not finding the objections given here to be a problem. I look forward to the STR vid response.

We forgive ya! And thanks for joining us in this discussion.

This is an interesting challenge here. Glad it got me thinking a bit. Now, perhaps this ground has already been covered… but what IS (ARE) the premise (or premises) that is (are) missing between premise 2 and the conclusion of the first syllogism? Surely it must be something like:

2b. The possible world in which God (perfect, or maximally great being) alone exists for all eternity is the best possible world.

But why should we think this to be true? Now Justin thinks that since this possible world contains all of the great-making properties to their maximal degree, then this is the best possible world. I can understand this, but is this the right notion of best possible world? It seems not. Why?

Because in this possible world, although there is the maximal degree of great-making properties QUALITATIVELY there are LESS great-making properties being instantiated QUANTITATIVELY than in some other world. In other words there is only ONE instance of goodness, not MANY. There is only ONE instance of love, not many… etc. But if God creates a world with other persons, then not only will there be ONE instance of goodness (and it will be maximal) but there will also be MANY OTHER instances of goodness (although they will not be had to the maximal degree. But if this is the case, then there is MORE (quantitatively) goodness than in the second world than in the first, in which case it is the second that is the best, and not the first. And now that I think about it, there is a possible world in which God exists and creates beings who never do wrong (at least atheists like Mackie have thought so…of course this has to do with the logical problem of evil tho, and I dont think that is right). But if this is so, then this possible world has a HIGHER (quantitatively) number of instantiated great-making properties to a HIGHER degree (qualitatively). AND there is no instance of non-great-making properties, so we could formulate it this way, and we actually have an argument FOR God’s creating persons. So I don’t think that Justin’s conception is right. Or at least it is not necessarily so.

So what we have is a struggle over how to define best possible world. I guess what Justin has to show is why the best possible world should be construed QUALITATIVELY only, and not also QUANTITATIVELY. I tend to side with Sam here in thinking of the best possible world, not as a world in which ONLY the great-making properties are instantiated to the highest degree, but a world in which the maximal amount (quantitatively) of great-making properties are instantiated to their highest degree (qualititatively) and in which on balance outweigh the amount of non-great-making properties. Something like that. But of course, if this is the correct conception, then the argument does not work.

Sorry for all of that mumbo jumbo and all the repetition. My thoughts were just spilling out. But I think this is very interesting. Thanks for sharing Justin.

Thank you Kevin for that VERY thoughtful reply! I too have always thought that my argument boils down to, among other things, that qualitative/quantitative distinction. I, however, also think we have good reasons for thinking that a maximally great being would not seek to sacrifice the quality or purity of the world on the alter of quantity.

Either way, I very much appreciate the response!

One quick note. I think you will find your 2b is actually premise 3 in the graphic.

Heck yeah dude! I like being challenged a bit and bouncing around ideas n such. Thanks for making me think hard about this and causing me to draw some distinctions. Take it easy.

Doesn’t the act of creation require a derivative result? Logically, a creator cannot create itself. Therefore, logically, anything that is not the creator is deficient to the creator in some aspect — that deficiency at a minimum being that the creation/creature was created while the creator was not.

Essentially, this entire argument seems to be an overly complicated proof that non-God things, by definition, are not God, i.e. that the created is not the creator. As my then 10-year-old daughter would say, “No duh!”

Not knowing why God created does not refute the fact that God did create. The asking of the question itself affirms that God created.

If God created something, it is not God.